The Hunger Strike is an ancient custom that has been used for solving serious personal and social conflicts for centuries. The concept was originally an option for fighting injustice and it remains so to this day. August 3rd, 2014, is the day Hunger Strike Commemorations in Ireland wind up for the year, which is a perfect time to learn about the tradition and some of the people who have carried it on.

The Hunger Strike was codified in the early Brehon Laws of Ireland and known as a Troscad. It was often employed against a chieftain or tribal leader by someone of lower standing and was carried out publicly on the abuser’s doorstep. Advance notice was given before commencing this type of strike and the defendant was supposed to fast along with the person who had the complaint. If the originator of the strike died of starvation their opponent had to pay relatives a fee and would be subjected to societal penalties and supernatural consequences. Few people allowed themselves to be shamed in such a situation for long and most conflicts were resolved quickly and without death. It turns out that forcing the other party to go hungry right along with you made a difference, as did the peering eyes of the public.

The Irish Republican hunger strike was resurrected in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising and was used to protest conditions in prisons and to change the political status of prisoners. In 1917, Thomas Ashe was the first to die on hunger strike, despite being force fed by the authorities. It was his second hunger strike in as many years and it only lasted five days. At the inquest into his questionable demise, the jury reprimanded the prison for the “inhuman and dangerous operation performed on the prisoner, and other acts of unfeeling and barbaric conduct”.

Prior to 1981, probably the most famous and beloved hunger striker was Terrence MacSwiney who was an author, an IRA volunteer and the Lord Mayor of Cork. He was arrested by the British for Sedition and spent 74 days on hunger strike before dying in prison. His struggle turned popular opinion against the English both nationally and throughout the world. Tens of thousands of people attended his funeral and the modern tradition of the publicized Hunger Strike was reborn.

Another widely covered hunger strike took place in 1972-73 when the British government refused to allow four Irish prisoners to be transferred to a jail in Northern Ireland. Delours Price, Marian Price, Hugh Feeney and Gerald Kelly were on hunger strike for 200 days and force fed by prison authorities for 167 of them. They were also put into solitary confinement and abused.

These named men and women were not the only people participating in these strikes and protests. Eamon De Valera and Thomas Hunter joined Thomas Ashe in his first hunger strike, along with other prisoners they commanded. Eleven men joined Terrence MacSwiney in 1920. Historically, female prisoners would strike in solidarity with the men but were never given the same recognition for their sacrifices. You would think that women starving themselves would have been a huge story but very little media attention was ever given to them. Adding insult to injury, often the chauvinism of the male leaders resulted in orders for the women to stand down.

In 1972, a massive hunger strike involving both male and female Republicans in numerous prisons in Britain and Ireland lasted for 26 days until William Whitelaw announced concessions leading to the political status the Republicans wanted. This arrangement was terminated 4 years later by the British Labor government when they insisted that all prisoners were criminals and not entitled to special status or their own clothing. It was an opinion that many still hold to this day.

The Republican response came in 1976. It began with Kieran Nugent a prisoner in the H blocks who refused to put on a prison uniform. He wore nothing but a blanket for years and more than half of the other Republican prisoners joined him. This blanket demonstration led to the dirty protests and to two different strikes. The revolt was ongoing for more than 5 years before culminating in what may be the most famous of all Irish hunger strikes in 1981.

The demands were simple and unchanged for all those years. The prisoners wanted political status. They also wanted to wear their own clothes, interact freely with others for educational and social purposes, have a visit, letter or parcel per week, and have their privileges restored from when they were protesting. The first hunger strike was led by Brendan Hughes. It began at the end of October in 1980 and female Republicans in the Armagh Women’s Prison joined that strike on December 1st. Just eighteen days later though, it was called off despite having no change in status.

Bobby Sands was the OC of the Republican prisoners in Long Kesh, after Brendan Hughes. Bobby had decided on another hunger strike and it was his idea to stagger the participation in order to keep it going as long as possible. This gave the media a grinding story of injustice and cruelty that seemed to last forever. He knew that public opinion was important and the coverage was going to be necessary. He warned all of his men that this strike would not be called off like the last. He started it himself, by refusing food on March 1st, 1981.

All in all 22 other men joined the hunger strike at various intervals. The support for the second strike was not as strong as the first until the death of Frank Maguire, an MP who left a vacant seat in the British House of Commons. The highly contested and extremely risky decision was made to put Bobby Sands on the ballot and the world suddenly paid a lot of attention to Northern Ireland and the hunger strikers. Coverage and pressure mounted internationally and when he won the election by over 500 votes, the prisoners, supporters and worldwide observers felt sure that Thatcher’s government would concede to their demands. They were all wrong.

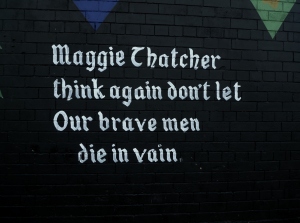

Margaret Thatcher refused to even entertain the notion of the prisoners’ demands. She dug her heels in and continued to criminalize the protestors, making incredibly cold and provocative statements in the days leading up to their deaths. Bobby Sands died of starvation as an imprisoned elected official a little over one month after he won the seat. His death and funeral were reported on every continent. Protests and boycotts all over the world against Thatcher and the British Government continued for weeks. Despite all the international pressure, nothing changed.

Nine other men died with Bobby over the next few weeks and months but still Thatcher would not budge. The hunger strike began to break when Paddy Quinn’s mother gave the authorities an OK to force feed her son against his wishes because she had no hope of a compromise from the British government and did not want her son to die. Other relatives soon followed her lead and the hunger strike was over. Only thirteen men survived out of 23 and Margaret Thatcher claimed victory over them all. The Guardian crowed, “The Government had overcome the hunger strikes by a show of resolute determination not to be bullied”. It was one of the only supportive reports in the world. Thatcher gained a reputation as a cruel and unfeeling robot of a leader and her decisions caused strained ties with several allies and a massive up-swell in new paramilitary recruits and activity.

Today there are countless memorials, statues, and murals throughout the North and the Republic dedicated to the long history of the Irish Hunger Strike. Many of them focus on the 1981 strike like the ones seen here – but it is important to remember that there have been many others throughout history as well. The men and women who did not gain fame from their incredible decision to undertake starvation for their own ideals should not be forgotten just because they lack a spotlight or didn’t actually perish. Though the memorials only count those who died, there were others who endured the same slow pain of starvation and their sacrifices should count too.

On this commemoration day, remember all of them. There are still prisoners worldwide who contemplate the same drastic option today that they have considered since the Celtic days of Brehon Law. It’s a shame that the forced starvation of your oppressor was left out of the tradition when it continued. If it hadn’t been, I imagine that there wouldn’t be so many names to remember on this day.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh tú.

[…] Hunger. […]